PaaS and Continuous Delivery - My 12 Month Journey

by John Turner

Posted on February 13, 2014

Continuous Delivery, Configuration Management, DevOps, PaaS

I have spent the past 12 months building out an enterprise Platform as a Service (PaaS) and Continuous Delivery (CD) capability. It’s been a challenging journey but one through which I’ve gained many valuable insights. We’ve created a very impressive capability that allows us to declaratively define application topologies and have that application delivered to production via a fully automated staged delivery pipeline. That’s quite a jargon filled statement but I’ll explain what it means throughout the rest of this post.

Before describing what we have been working on and the capability we have created, I wanted to talk about why we set out to build this capability.

In The Beginning

My background is in application development; specifically, I have worked most of my career in Java development building enterprise Java applications in their various forms and guises. Throughout this time, the way in which I’ve seen development, operations and infrastructure teams interact has been very much the same. The interactions have been dictated by the organisational structure and within that organisational structure the goals and activities of those groups have been very poorly aligned.

The widespread adoption of agile methodologies has seen organisations focus predominantly on the alignment of ‘the business’ and the development functions they depend upon. As a result, there have been significant steps made toward building a shared understanding of the business objectives and how development functions deliver upon those objectives.

Using process mapping systems such as Kanban, it is relatively trivial to demonstrate the impact of this alignment on the flow of work through development as the bottlenecks within the organisational system change over time.

The result of this insight was that we targeted the bottlenecks that related to software build activities (i.e. within our area of comfort and control). This further exacerbated the turbulence in the flow of work related to software delivery activities. Importantly, Kanban allowed us to identify and quantify the impact of those bottlenecks on the efficiency of the organisational system as a whole.

Where Next

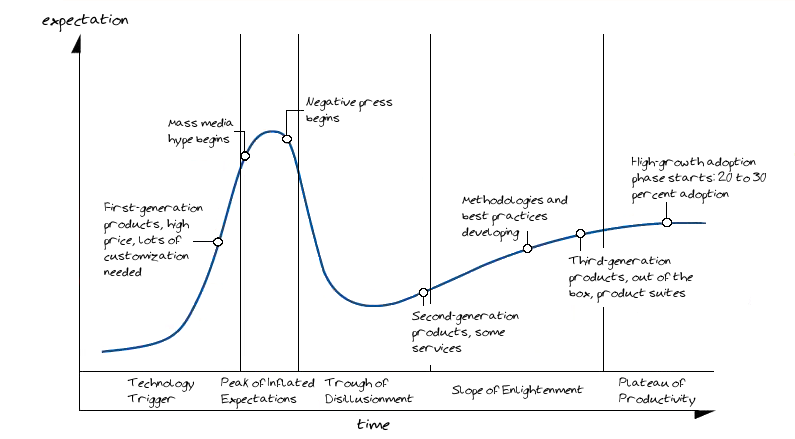

With all the hype (and I could say hysteria) around DevOps and the particularly compelling tagline that ‘DevOps finishes what Agile started’ it was something I took particular interest in. There is lots of commentary and opinion as to what DevOps means but much like agile there is no clear roadmap to adoption.

For the record, I believe DevOps to be any initiative with the aim of increasing alignment between the development and operations capabilities of an organisation. It is also a culture where the delineation between the development and operations teams is less pronounced with increased sharing of roles and responsibilities.

What we needed to streamline the flow to production was to:

- Automate the build and deployment of software.

- Automate and enforce the quality assurance process.

- Automate the promotion of software between environments.

- Increase the consistency between environments and across systems.

This level of automation reduces handovers, increases consistency and reliability, and streamlines the flow to production. The process itself also creates a common vocabulary between development and operations (more about this later).

The most common approach to DevOps seems to be simply throwing the development and operations capabilities into a single autonomous team and leaving them at it. This approach has some merit but are we really going to get the increased consistency between environments and across systems with this approach? We might if we employ ‘Communities of Practice’, but a better approach would be to employ sets of tools and practices that are shared across the organisation. Better still; deploy those tools as part of a platform that enforces a commonality of approach.

It’s important to understand what we gain and what we lose from taking this approach as opposed to the ‘throw development and operations together’ approach.

Utilising a PaaS we win because:

- We get economies of scale through tools etc. that are leveraged across the organisation offering the potential of a greater ROI.

- We get a single point at which we can provide governance (e.g. all pushes to production must be approved by the duty manager).

- We get consistency across projects and all that it brings.

Using a PaaS we lose because:

- We are mandating the use of specific tools and technologies.

- We are enforcing a rigid application build and deployment lifecycle.

- We lose the benefits of a Darwinian evolution of tools and technologies.

We chose to adopt a PaaS capability with specific focus on being as open as possible so that we are not unnecessarily mandating the use of specific tools and technologies.

PaaS: Build or Buy?

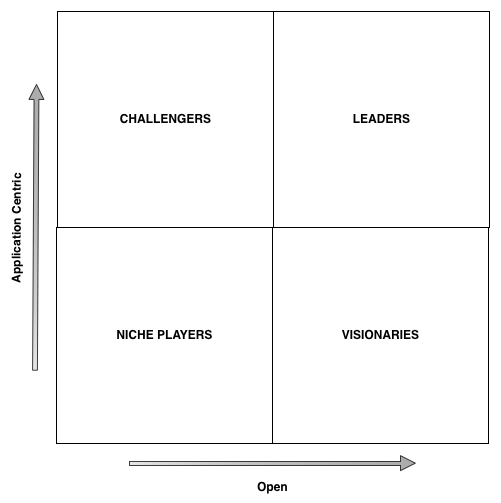

Very early in our evaluation of PaaS providers we started to look at PaaS along two dimensions. I’ve depicted these axes using the Gartner Magic Quadrant methodology below.

In my view, the majority of the offerings from existing hardware or virtualisation providers played very much in the bottom left quadrant. There were quite a few new entrants playing in the right and top right quadrants but therein lies the problem. PaaS in general is very immature and there is significant fragmentation and little standardisation in this space. So to make a buy decision on the right hand side of the Magic Quadrant is quite a punt.

My decision was to build our own PaaS but to leverage established toolsets to provide the majority of the functionality (I’ll get into this a bit more later!). This way we are not reinventing the wheel but are also maintaining the ability to change direction with a lower cost of divorce than we would have with a full stack vendor solution.

Continuous Deployment or Continuous Delivery?

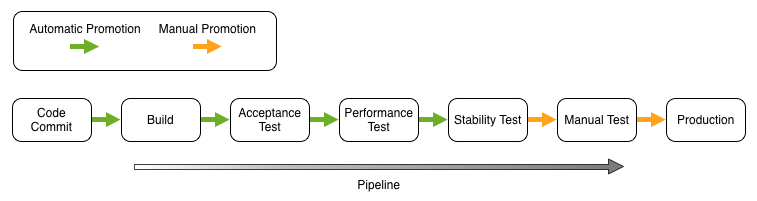

An early mistake was to allow a misunderstanding to develop around Continuous Deployment and Continuous Delivery. The vision for our initiative was to facilitate either but the objective was to implement a continuous delivery pipeline.

The difference between them is really quite simple; the implications are not so trivial.

When implementing Continuous Deployment all of the stage transitions (arrows) are fully automated with automatic promotion from one stage to the next. When implementing Continuous Delivery, all stage transitions are fully automated but require manual promotion for a number of the stage transitions. Typically, Continuous Delivery requires that the final promotion to production be manually triggered.

Broadly speaking, when implementing a Continuous Deployment pipeline the level of rigour around quality assurance, audit, runtime monitoring, anomaly detection etc. is far more onerous.

But what did we actually build?

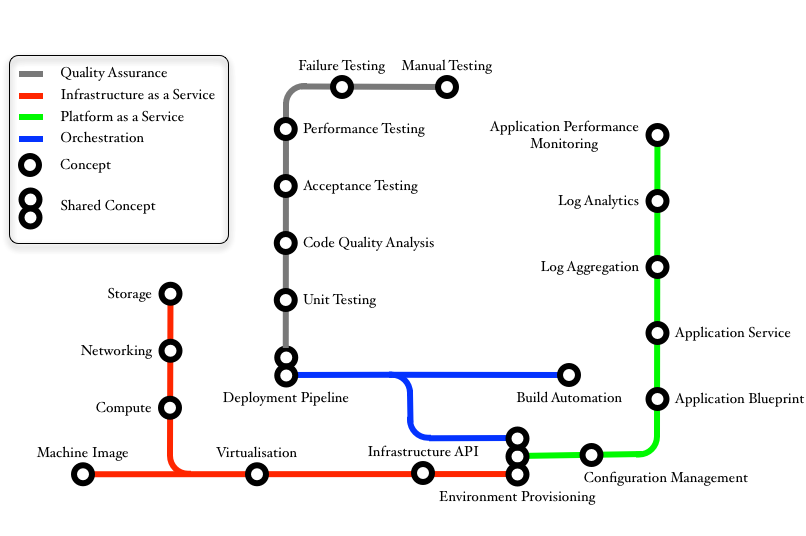

The complexity of PaaS, Continuous Delivery and all that surrounds it is equal to the number of moving parts multiplied by the amount of jargon that surrounds it. I hope I have not added to it but if I have, I think this concept map will help bring clarity.

I’ve depicted the four main themes with which I have worked over the past 12 months. Within those themes, I have identified the concepts as well as concepts that are shared. I’ll iterate through the main concepts we have worked on.

Deployment Pipeline

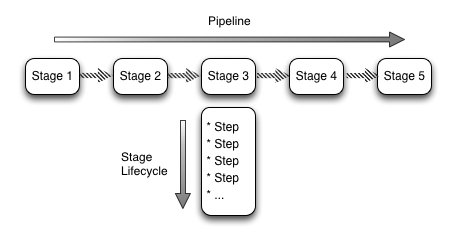

When we speak about the deployment pipeline it immediately brings to mind the implementation and all the details that go along with it. However, one of our objectives was to be language runtime agnostic and so in reality we would be developing a number of pipeline implementations. The most important thing for us was to define the lifecycle of the staged delivery pipeline.

Our staged delivery pipeline looks very much like Figure 5. The stages might include:

- Code Commit

- Build

- Acceptance Test

- Performance Test

- Stability Test

- User Test

- Operations Test

- Production

As an example, the stage lifecycle of the ‘Build’ stage might include:

- Checkout

- Build

- Pre-Unit Test

- Unit Test

- Post-Unit Test

- Pre-Integration Test

- Integration Test

- Post-Integration Test

- Publish Test Result

- Static Code Analysis

- Version Artefact

- Notify

It becomes quite easy to see how this staged build pipeline might be implemented for any of the popular Continuous Integration (CI) servers. It also becomes clear how you might bind to a language runtime via build tools such as Maven, Rake etc. It’s not surprising that similar build, dependency management, test and code analysis tools exist for Java, .NET, Ruby, PHP etc. We have also found that good CI server plugins, Sonar plugins and Artifactory support exists for that majority of these tools. Where they don’t exist we have written our own.

An important element of the pipeline is that each stage executes within a context that is derived from 1) the provisioned topology and 2) the configuration management data. For example, if I have a service that needs to explicitly know the IP address of all other servers in an application service tier this information is provided via the context.

Machine Image

You may wonder why, of all the concepts on the map, I chose to highlight the ‘Machine Image’ concept. The way in which you manage machine images and their configuration falls into the ‘bake or fry’ debate. Baked servers come fully pre-configured and are ready to boot and start serving requests. Every flavour of server in your estate will require a corresponding image so increasing the image storage requirements. The benefit of this approach is that servers require zero configuration post boot so are faster to provision and start.

Fried servers come with ‘just enough OS’ and a configuration management tool is used to apply software and configuration. This approach has minimal image storage requirement with the drawback being that the post boot configuration makes provisioning and starting services much slower.

Companies like NetFlix use a ‘bakery’ that bakes servers on demand, caching a machine image as long as it is required. This is a middle ground between the two approaches and suits the NetFlix environment as they have a number of very large clusters (i.e. the ratio of machine instance to machine image is quite high).

We don’t tend to have ‘very large’ clusters so the bakery approach does not make a lot of sense. We also have a ‘large’ number of different server configurations so baking servers would require quite a lot of storage. We also don’t have any requirements to spin up servers on demand (i.e. in less than 2 minutes) so can absorb the cost of frying servers.

Configuration Management

Each stage of the staged delivery pipeline that provisions an application environment has an associated environment defined within the configuration management tool (in our case Chef). We tend to think of configuration existing within a hierarchy:

- Defined by the platform, cannot be overridden.

- Defined by the platform, can be overridden.

- Defined by the development team, cannot be overridden.

- Defined by the development team, can be overridden.

- Defined by operations.

This hierarchy helps to achieve consistency where required but also allows flexibility. For example, we typically deploy tomcat servers in the same way but some applications use JNDI or JMX and they require the flexibility to deploy additional services or resources. In our case, this is achieved declaratively by specifying this information within the configuration management tool.

Application Blueprint

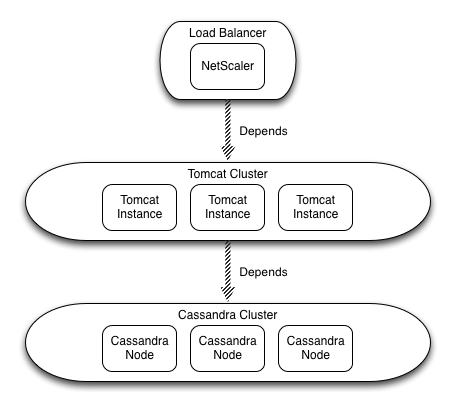

The ‘Application Blueprint’ is a term we borrowed from the guys at GigaSpaces. This is how they refer to an application as deployed via Cloudify. While we don’t use many of the Cloudify features, we do use it to manage the dependencies between ‘Application Services’ and to stereotype the nodes as they are being provisioned. We also abstract our use of Cloudify from the consumers of our PaaS services for the reasons I identified earlier (i.e. cost of divorce should the PaaS marketplace start to converge).

Note: Each cluster represents an application service tier and each instance (or node) represents an application service. The dependency relationship is a directed graph as opposed to a tree as Figure 6 depicts.

The Application Service

Application Service is another term borrowed from Cloudify and refers to a distinct service. For example in Figure 6 Tomcat and Cassandra are both Application Services.

From an implementation perspective, a top level Chef recipe corresponds to an Application Service. Of course, a top-level recipe is a composite of other recipes. Interestingly, we use the same pipeline to develop and promote Chef recipes as we do for any other software artefact.

Environment Provisioning

Entire environments are provisioned and un-provisioned as part of the lifecycle of a number of stages within the delivery pipeline. The environment information (e.g. IP addresses of nodes etc.) is exported to the execution context and is then available to the configuration management tooling, test infrastructure etc. As a result all servers are considered immutable (see Fowler on Immutable Servers).

A negative side effect of this is that the number of nodes provisioned and un-provisioned in this manner dictates the cycle time of the pipeline. We don’t see this as a problem because we believe in the Single Responsibility principle (i.e. if your deploying lots of nodes to test an application, the application is probably doing too much!).

Shared Services

My fingers are now bleeding so I want to wrap this up, but I can’t finish without tipping my hat to some of the shared services we have evaluated and implemented recently.

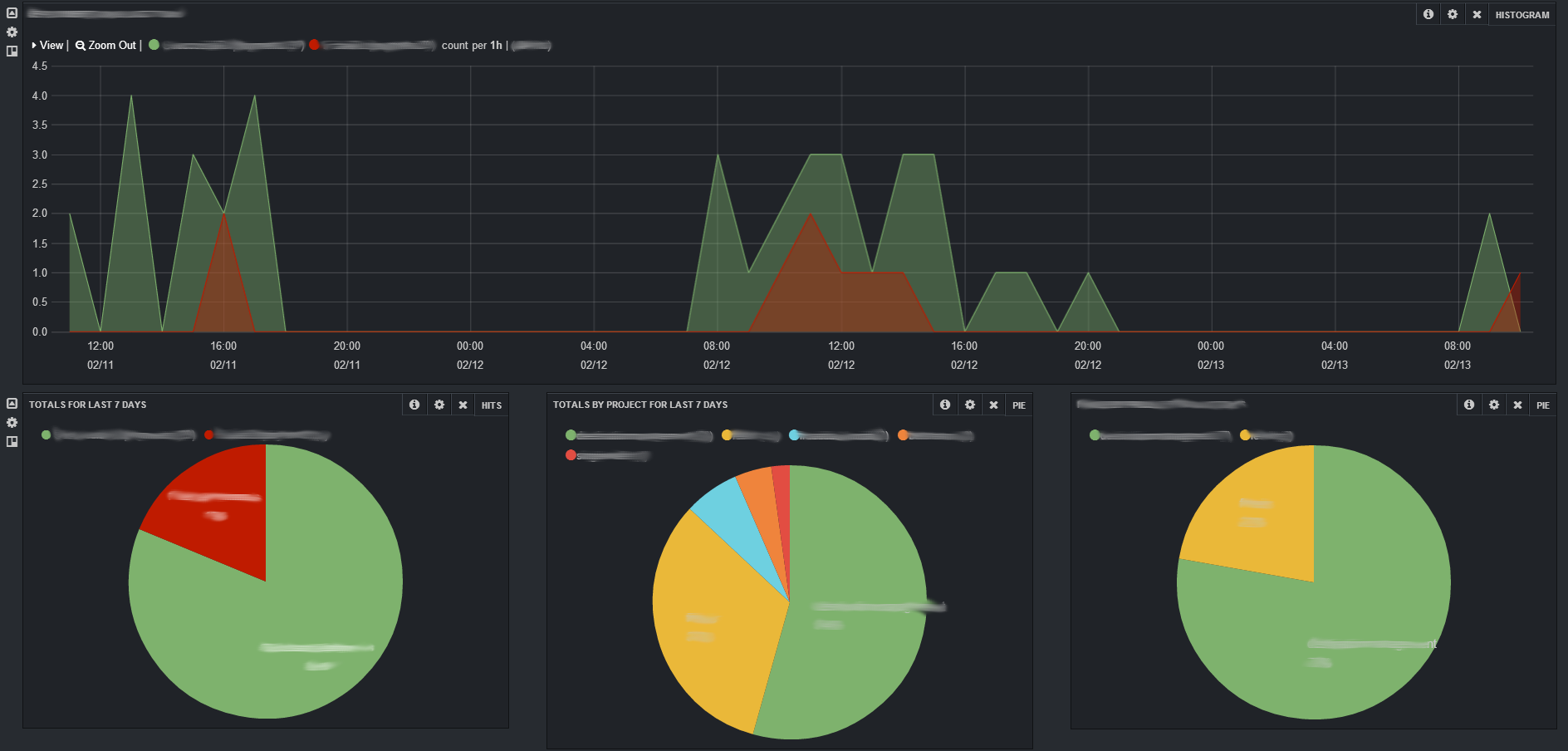

The first is Log Aggregation and Log Analytics. Because many of our environments are transient, shipping logs (i.e. aggregation) is really important. Using Logstash for log aggregation has the added advantage that not only does it support aggregation and search but it also supports building dashboards via Kibana to provide additional insight. The PaaS itself uses Kibana in this way.

The second such service is Application Performance Monitoring (APM). In its best form, agents intelligently and dynamically instrument the code to extract monitoring information. This creates great insight during the build, test, deploy and execute phases of the application lifecycle.

I mentioned at the beginning that we saw this initiative as an enabling platform for DevOps. Shared tooling enables DevOps by creating a common language and window onto the application.

Lights out on 2013!

It’s lights out on 2013 and it’s been good to reflect on what has been achieved. It’s been an interesting and challenging year and I’ve been very fortunate to work with a great team on all of the above. Roll on 2014!!

I hope this has been useful and I would love to hear any questions you might have or read about your PaaS or Continuous Delivery story.